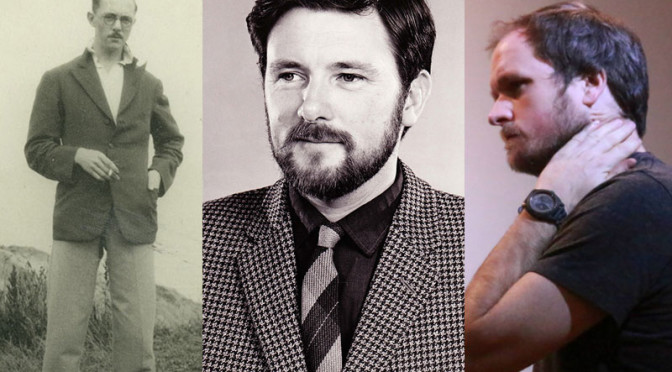

Penicillin was discovered in 1928 but was not made widely commercially available until 1942. This is how my grandfather and namesake Robert Francis Penty came to die of scarlet fever in 1936 leaving behind his wife Frances, pregnant with my father. I think that any concept I have of masculinity comes from my father’s benevolent nihilism and I always wondered if not having a dad himself made him so atypically dad-like.

He was part of a specific English generation. He was slightly older than the hippies and mods (he was already in his thirties when Sgt. Pepper’s came out) and far too young to have fought in World War II. He hid from bombs in the basement with his mother and grandmother and his food was rationed until young adulthood and, as a consequence, he had a somewhat numb view of war and world affairs. When I was so scared living in post 9/11 New York, my father wasn’t particularly impressed. “Well,” he said, “the world is defined by war.”

Christ, Dad.

My father’s name was also Robert but we have different middle names. His was Anthony. So, I am not a Junior and where my father went by Bob, I am Rob. My grandfather apparently also went by Bob and my grandmother wanted her son to be Robert. She even told me she said that during labor. “He’s going to be Robert, not Bob.” So his cousins always called him Robert, the same way my cousins call me Robby.

But were the phrase “Hey, I’m Bob and this here is Bob Junior” ever spoken by my dad, it would have been so out of character for him and for our relationship. Bob is such a regular guy name yet my father was not a regular guy, with the emphasis on guy. There are a lot of standards that we have for guys, for men, for dudes, bros, dude-bros, and also dads.

One of my friend’s fathers looked like Mike Ditka and called us all “tiger.” Another friend’s dad was a Viet Nam vet turned stock broker who drove a Porsche.

My father never hosted a barbecue or made a show of his work on our grill. He never screamed at a television due to a sporting event. He never threw me a baseball. Being English, I wonder if he ever threw a baseball anywhere or at anything in his life. He never taught me to change a tire. He never took exceptional pride in an automobile or a deck, man cave, or stereo system. He accompanied me on a father son Boy Scout trip once, though he wasn’t outdoorsy. He never gave me “the talk.” He didn’t give me my first beer. He didn’t teach me how to ride a bike. I actually taught myself one day at a friend’s house and I remember telling him and he said, “huh, I always thought I would be able to teach you.”

I saw him high five a stranger at a hockey game once. I myself gave my father five on, I believe, two occasions. Both times his arm was bent rigidly at the elbow, palm flat and it was as if I was slapping a diving board.

“You wait until your father gets home!” was never a threat in my household. My father was far too reasonable. He had a PhD and went about his routine with the regularity of a metronome. He rose early and, to my knowledge, never slept past 7:00 AM. In his final years he was in a church prayer group and he called each of the men on Friday night to remind them. At his funeral these men introduced themselves to me by the time at which he called them. I’m Jim, your father called me every Friday night at 8:15. Hi, I’m Bill, your father called me at 8:20 and so on. My mother told me that my father spanked me once for running out into the street in front of a car. I don’t remember the incident but, honestly, I’ve gotta side with the old man on that one.

He was different than the other men, I noticed, when I would observe him at gatherings, usually at his Rotary club. He didn’t speak when he didn’t have anything to say. He was often off to the side, not “one of the guys.” I inherited this tendency from him and complained that it was so hard to just join in sometimes. “We’re not hail fellow well met,” he told me.

Christ, Dad.

I did eventually learn to ape the customs of the modern male. I joined a fraternity. I’m adept at using context clues so I know just how shocked I should be at a fantasy football trade. I think I learned about baseball just to be able to join in and participate in those Monday morning water-cooler conversations with other men.

And yet I am my father’s son. I have his hands. I have his posture. I read a book the way he did, resting it in my lap, resting my head in my left hand. From time to time I catch myself listening to some other man speak, over a beer perhaps, about a business deal or the best contractor for an addition or any other innumerable things about which I truly don’t care and I find myself smiling and nodding politely. He never taught me how to brag or how to bullshit and I’ll always love him for that.

In the most American father son ritual of all – little league – my father gave the oddest encouragement. I used to cry when I struck out and my father explained to me, like the engineer that he was, that I must examine problems such as this and return to them in order to make incremental improvements to ultimately move past them.

Christ, Dad.

And yet, that is the authentic voice of my dad, the voice I carry with me.

I wonder what would have happened if my grandfather had lived. My father and his parents would have stayed in Leeds. Perhaps my grandfather would have gone to fight in World War 2 and died there. Or maybe not. Maybe my father would have had siblings. Maybe he would have avoided the sadness of his childhood and never would have felt the urge to move to America.

But that’s not what happened. What happened was that my grandmother moved back to her home city of Sheffield where there would be extra help for her to raise her son. She didn’t go to therapy or think about her journey. She just went because she had to.

At thirty-eight I’m older now than my grandfather ever got to be. If I could meet him in some Field of Dreams scenario what could I tell him about my life? I live in America. I’m not married. I have no children. I haven’t fought in war, nor ever experienced one in my country. Can one call oneself a man without having been through any of those things? What would he think of my blog or my improv team or my career? The inter-what now? Net?

Or maybe we would have a tender yet manly scene where we size each other up, look each other in the eye and, neither one of us daring go for the hug, we shake hands. I say, “you know that son you never got to meet? I just want you to know that he was a good man.”

My grandfather and namesake would be moved, perhaps a tear would gather in the corner of his eye and roll down his cheek. He’d thank me and then say something full of symbolism and manly restraint, like, “you’ve got a nice handshake, son, a nice firm handshake.”

And then I could call after him, “Grandpa, do you want to have a catch?” And he’d say, “Um, not particularly, that’s not really my thing.”

Rob, it was very interesting to connect with you via Facebook. I contacted your dad in 1999 when I learned about him from Norman Penty in England, the man who has tried to organize a worldwide genealogy of the Pentys. Your dad wrote me about his English origin and suggested we visit him if we were ever near Rochester. I happened to be looking at this correspondence today and wondered why we had never followed up on his suggestion. We have a daughter in Ithaca, so we do go there frequently. So I found you on Facebook and was sorry to learn that your dad had died 7 years ago. But I learned a lot about him from your essay. Please send me your email address. Perhaps we can keep in contact and get together sometime when we are in NYC. We are a retired couple living in Ann Arbor.